by Arnoldt | Aug 10, 2021 | latestnews

What is the purpose of marking correspondence “without prejudice”?

The general position is that without prejudice correspondence is inadmissible in court. The term “without prejudice” means without the loss of rights. Ordinarily when parties attempt to settle a matter, such correspondence would be marked “without prejudice”. The purpose of this is to guard against an argument by one party that a concession made or offered in bona fide without prejudice negotiations constitutes a waiver of a right or an admission of liability by the other party.

It therefore affords parties to a dispute the opportunity to explore the possibility of settlement of a matter without the risk of such discussions (regarding possible concessions of liability or a party being prepared to pay a certain sum of money to the other) being placed before a court.

In instances where parties have not marked correspondence “without prejudice” but the purpose of the correspondence and the true intention behind such correspondence is to make a genuine attempt to settle a dispute, then such correspondence would not be admissible in court.

Can any correspondence or document be marked “without prejudice”?

No! Often lawyers and lay-people misconstrue the purpose of marking correspondence “without prejudice”. It is not uncommon to see confidential correspondence or correspondence that is simply related to legal proceedings marked “without prejudice” when it should not be. Unless such correspondence has been addressed in a legitimate attempt to settle a matter, simply marking correspondence as “without prejudice” does not guarantee that it cannot be placed before a court.

To this end there is case law from the former Appellate Division. It was held that “the purpose for which a party desires to adduce a “without prejudice” communication is all important, for in exceptional circumstances it may well be admitted in evidence despite the general rule in order to prove, for example, that it contains a threat, an act of insolvency, or possibly other matters that it would be contrary to public policy to protect it from being admissible.”

It follows that a party may not use “without prejudice” correspondence to attempt to conceal information from a court. Furthermore, privilege over that correspondence may be waived if, despite being marked “without prejudice” or a genuine attempt to settle a dispute it contains information that is: threatening; in the public interest; causes prescription to start running on a claim or amounts to an act of insolvency.

Written by: Letoya Francis, Associate Eversheds Sutherland.

by Arnoldt | Jul 27, 2021 | latestnews

By GRANT WILLIAMS, TYRON FOURIE And SIBULELE SIYAYA

The newly enacted Cybercrimes Act (“Act”) not only creates offences but also codifies and imposes penalties on cybercrimes and defines cybercrime as including, but not limited to, acts such as: the unlawful access to a computer or device such as a USB drive or an external hard drive; the illegal interception of data; the unlawful acquisition, possession, receipt or use of a password; and forgery, fraud and extortion online.

The Act criminalises the disclosure of data messages which are harmful and the disclosure of data messages that contain intimate images and seeks to implement an integrated cybersecurity legislative framework to effectively deal with cybercrimes and address aspects pertaining to cybersecurity.

The Act creates 20 new cybercrime offences and prescribes penalties related to cybercrime. It provides overarching legal authority on how to deal with cybercrimes, by regulating how these offences must be investigated which includes searching and gaining access to, or seizing items in relation to cybercrimes.

Section 3 of the Act makes provision for offences relating to personal information (as defined in the POPI Act) including the abuse, misuse and the possession of personal information of another person or entity where there is reasonable suspicion that it was used, or may be used, to commit a cybercrime.

It provides for the establishment of a 24/7 point of contact for all cybercrime reporting, the establishment of various structures to deal with cybersecurity (which includes a cyber response committee, a cyber security centre and a national cybercrime centre).

The Act imposes an obligation on electronic communications service providers (“ECSPs”) and financial institutions, such as banks, to report cyber offences within 72 hours of becoming aware of them. They must preserve any information which may be of assistance in the investigation and they are required to work with law enforcement, where applicable, in the investigation of cybercrimes. In certain instances, this may involve the handing over of data and hardware. ECSPs and financial institutions must report cyber offences without undue delay and within 72 hours of becoming aware of them, failing which, they may be liable to a fine of up to R50,000.

The Act provides the South Africa Police Services with the authority to not only investigate, search, access and seize but to also co-operate with foreign states to investigate cybercrimes. Further, the National Director of Public Prosecutions is obligated, in terms of the Act, to compile a report on the number and results of prosecutions for cybercrimes for the National Prosecuting Authority.

The Act further affords South African courts with jurisdiction to adjudicate over any act or omission alleged to constitute an offence under the Act and affecting a person in South Africa, even in instances where such a defined cybercrime is committed outside of South Africa.

More importantly, the Act prescribes certain sentences for offenders, which entail fines ranging from R5 million to R10 million and/or imprisonment ranging from 5 to 10 years, with other more serious offences attracting imprisonment of up to 15 years and an imprisonment period not exceeding 25 years for computer related terrorist activity and related offences. The Act imposes lesser sentences for the dissemination of data messages which advocates, promotes, or incites hate, discrimination, or violence to imprisonment not exceeding 2 years, or a fine.

The courts have also been afforded with a discretion to impose any sentence that it deems appropriate under section 276 of the Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977 to anyone that is found guilty of cyber fraud, cyber forgery and uttering.

Individuals will need to educate themselves and be very careful when corresponding, especially over social media. Companies, especially ECSPs and financial institutions, will need to initiate training and programmes to ensure compliance with the Act.

by Arnoldt | Apr 21, 2020 | Uncategorised

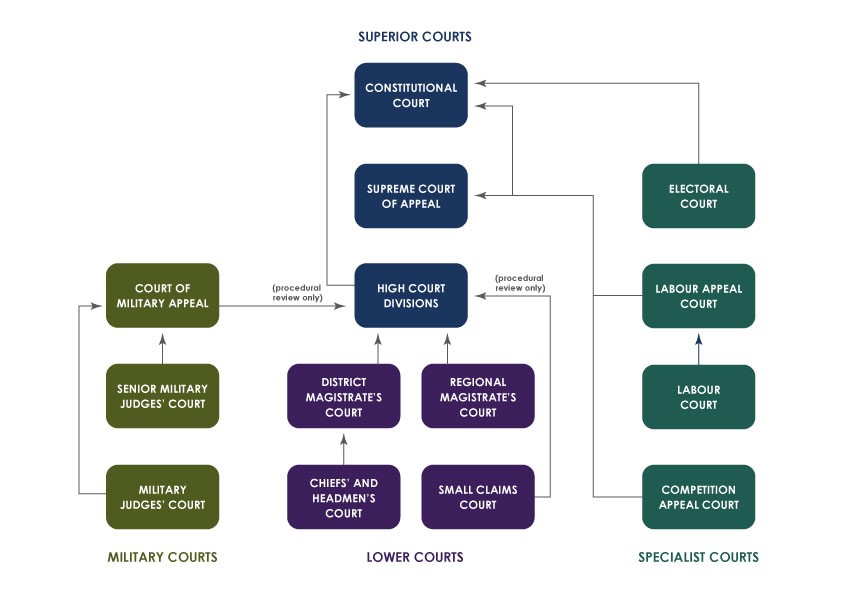

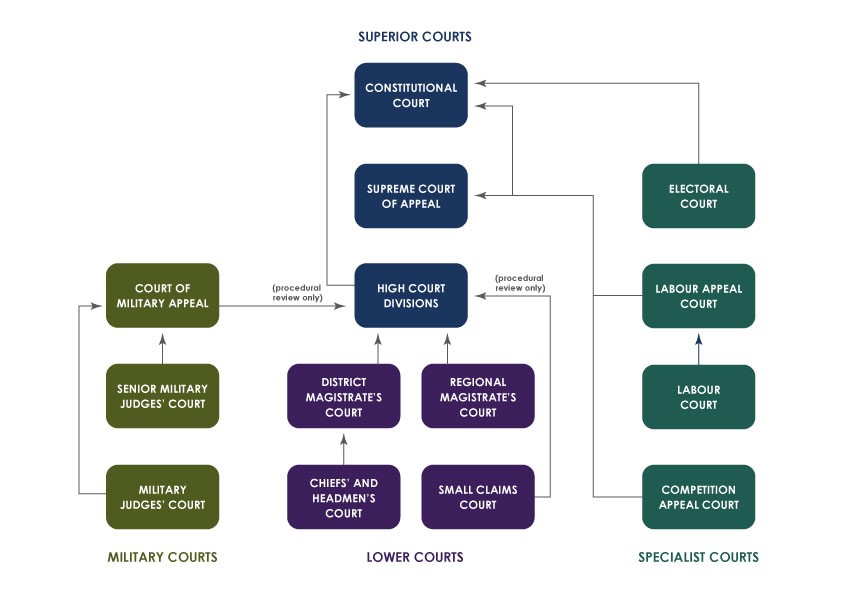

South African court types and levels

South Africa’s lower courts

Chiefs’ and Headmens Courts

Chiefs’ and Headmens Courts administer African customary law, subject to the Council of Traditional Leaders.

Small claims courts

Small claims courts hear civil cases involving claims below R15,000.

Usually these claims are brought by individuals rather than companies. For example, they may involve claims for money or goods that are owed, claims for damages or claims based on violations of contract terms.

Magistrates’ courts

Magistrates’ courts are divided into district and regional courts.

District courts hear civil matters involving claims below R200,000 and less serious criminal cases, involving offences other than rape, murder or treason.

These courts can impose fines up to R120,000 and prison sentences up to three years.

Regional Magistrates’ Courts hear civil cases involving claims below R400,000. They also hear less serious criminal cases and divorce cases.

A regional Magistrate’s Court can impose fines up to R600,000 and give prison sentences up to 15 years.

South Africa’s High Courts

South Africa includes ten provincial High Courts and three local High Courts. Each of these presides over a different jurisdiction.

High Courts hear civil cases involving claims of R400,000 or more, as well as criminal cases involving rape, murder or treason.

The High Court system also includes circuit courts. These move around the country to serve more rural areas.

The Supreme Court of Appeal

The Supreme Court of Appeal is an appellate court. It hears appeals against rulings that are sent to it by the High Courts.

The Constitutional Court

The Constitutional Court is the highest court in South Africa. It hears appeals that relate to the Constitution only after a judgement has already been handed down.

All other appeals go to the Supreme Court of Appeals.

No other court can overturn a ruling made by the Constitutional Court.

Specialist courts

A number of specialist courts handle matters in specific areas of law. For example, these include Tax Courts, Labour Courts, Land Claims Courts and Electoral Court.

These courts are similar in status to the High Courts.

Military courts

The military courts hear cases involving members of the South African National Defence Force, who are subject to the Military Discipline Code.

Which South African courts hear personal injury cases?

Cases involving personal injury claims below R400,000 are heard by Magistrates’ Courts.

Cases involving higher claim amounts are heard by a High Court. A High Court also hears appeals against rulings by Magistrates’ Courts.

by Arnoldt | Apr 11, 2020 | News and Info

How cryptocurrency Ponzi schemes work

At their cores, most cryptocurrency Ponzi schemes are just old-fashioned Ponzi schemes wrapped in the modern, high-tech veneer of cryptocurrency. While the cryptocurrency lingo can be confusing, the schemes themselves are relatively easy to understand. Generally, the fraudsters solicit investments in a cryptocurrency-related business, promise high returns in a short period of time and use the contributions of later investors to pay off earlier investors. At some point, the fraudsters stop making payments and abscond with their investors’ money.

In the BitClub Network case, the defendants offered investors shares in cryptocurrency mining pools. Cryptocurrency mining is the process of verifying previous cryptocurrency transactions in exchange for potential rewards of cryptocurrency. Through cryptocurrency mining, individuals can earn cryptocurrency without having to buy it. However, the cryptocurrency mining process is costly, time-consuming and rarely profitable. It is more likely to be successful when multiple people work together in groups called cryptocurrency mining pools.

From 2014 to 2019, the BitClub Network used online videos and presentations in multiple countries to recruit thousands of investors. The defendants promised high returns in a short period of time, as well as financial incentives for recruiting new investors. According to the defendants, investors would be paid a percentage of the profits from the Bitcoin mining pools operated by the BitClub Network. In reality, internal communications showed that the payment amounts were arbitrary and unrelated to the performance of the mines. To encourage investment in the BitClub Network, the payouts to early investors were very high and they decreased consistently thereafter. However, the defendants knew that the payouts were still too high for the enterprise to be sustainable on a long-term basis. Meanwhile, according to the DOJ, the defendants spent their investors’ money “lavishly.”

by Arnoldt | Nov 12, 2019 | latestnews, News and Info

There has been some confusion as to the charge of THEFT BY FALSE PRETENCE.

I personally accepted that the said offence forms part of what we collectively referred to as Commercial crimes, being fraud, forgery, uttering, theft by false pretences, theft and corruption.

During investigations whereby I could identify the named crime, SAPD will refuse to accept such allegation and would confirm that any case with an identified offence involving theft by false pretences must be referred to as fraud. Should the prosecutor decide to prosecute, it will be prosecuted as fraud, and should the prosecutor decide not to prosecute, a civil claim could be initiated.

Further, numerous investigators still refer to theft by false pretences as an easy alternative to fraud despite not being a competent verdict on a charge of either theft or fraud or vice versa. However, see S v Mia and Another 2009 (1) SACR 330 (SCA) where the SCA held that theft by false pretences is, in fact, a competent verdict on a charge of robbery.

Jonathan Burchell holds the following view in South African Criminal Law and Procedure, 4th ed, vol 1 at chapter 14, 237:

“In the case of theft it is contended that a taking is invito domino (without the owner’s consent) unless the consent is real and that consent is not real for the purpose of the criminal law if it is induced by fraud whether or not intention to pass ownership is nullified. Where X induces Y to hand to him R200 on the pretext that he will bank it for him and X makes off with the money, it is theft (even though it is also theft by false pretences and fraud) because, although Y consents to hand over the money, he does not consent to X stealing it.”

Fraud is defined by Snyman as follows:

“Fraud is the unlawful and intentional making of a misrepresentation which causes actual prejudice or which is potentially prejudicial to another.”

And further defines the offence of theft by false pretences as follows:

“A person commits theft by false pretences if she unlawfully and intentionally obtains movable, corporal property belonging to another with the consent of the person from whom she obtains it, such consent being given as a result of a misrepresentation by the person committing the crime, and appropriates it.”

Snyman describes the elements of the crime to be the following:

“(a) a misrepresentation (b) actual prejudice (c) a causal link between the misrepresentation and the prejudice (d) an appropriation of the property (e) unlawfulness and (f) intention.”

Kruger A, Hiemstra’s Criminal Procedure, issue 9, summarises the differences of opinion of our courts and authors pertaining to the crime of theft by means of false pretences as follows;

“There is a difference of opinion on whether a finding of “theft by means of false pretences” is competent on a charge of theft. The concept was correctly described by Van den Heever J in S v Mofoking 1939 OPD 117 as a deformed legal concept and by De Wet in Strafreg 4th ed at 416 as a monstrosity. The offence is nothing other than fraud. Hunt Criminal Law II at 754 calls this a “shadowy and ambiguous crime.” He says it is fraud, although not called such. The Free State High Court in S v Kudjiwane 1975 (3) SA 335 (0) unambiguously decided that on a charge of theft no finding of theft by false pretences is possible. One consideration in coming to that conclusion was that theft by false pretences is a more serious crime than theft simpliciter because false representations are added. The prosecutor should simply see to it that theft is charged according to the facts or that, if there was a misrepresentation, fraud is charged.”

“In the Transvaal Provincial Division, the origin of the view that such finding is possible is in R v Hyland 1924 TPD 336. The correctness of this view was doubted in several cases discussed in R v Levitan 1958 (1) SA 639 (T) where the Hyland principle was grudgingly accepted. In S v Stevenson 1976 (1) SA 636 (T) the designation of the offence was rejected obiter. The Natal High Court has not rejected the offence, as either an eo nomine offence or as a competent verdict (R v Teichert 1958 (3) SA 747 (N); S v Nkomo 1975 (3) SA 598 (N)). The view in the Natal Provincial Division is that the particulars of the false pretences must be given otherwise the accused would be prejudiced.

It is submitted that the offence eo nomine is unnecessary and that it is not a competent verdict on a charge of theft because section 264 does not authorise it, nor does section 270 because it is a wider offence than theft. The charge should simply be fraud.”

Snyman states that the “(C)riminal law would be none the poorer if this crime were discarded.” The author submitted that it would not be satisfactory to treat all cases of theft by false pretences simply as cases of fraud and that the best way of treating such cases would be to charge the accused with ordinary theft, but to include a specific allegation in the charge sheet to the effect that the accused obtained the property as a result of false pretences.

For this submission, the author relies on Levitan and Teichert supra as well as S v Knox 1963 (3) SA 431 (N) and S v Salemane 1967 (3) SA 691 (O). Snyman’s approach is supported by Du Toit et al, Commentary on the Criminal Procedure Act, service 56, vol 1 at 26-17.

The aforementioned views of Kruger, Snyman and Du Toit should not be viewed in isolation and it is necessary to consider the Free State judgments of Salemane and Kudjiwane. In Salemane the court accepted that theft by false pretences as a crime eo nomine existed but stated that theft simpliciter was sufficiently wide to include theft by false pretences and that accused persons could be successfully charged with theft even where the State relies on false pretences. Where evidence of false pretences is available, the prosecutor may choose in a judicious manner whether to charge in respect of theft or theft by false pretences. If the prosecutor decides to proceed with a charge of theft, the court must consider with a view to prejudice whether the accused is entitled to further particulars, even if he does not ask therefore.

In Kudjiwane the Free State High Court accepted the correctness of the reasoning and conclusions in Salemane at 336E-G, but concluded that insofar as theft by false pretences includes an element of falseness, it is a more serious crime than theft and therefore a conviction of theft by false pretences is not permissible on a charge of ordinary theft.

Supreme Court of Appeal in S v Mia and Another 2009 (1) SACR 330 (SCA).

In this judgment the SCA found that theft was a generic offence that encompasses theft by false pretences. The court found that although fraud was not a competent verdict on a charge of robbery, it was competent for a court to convict an accused on the competent verdict of theft where the charge is one of robbery.

Clearly it is competent for a court to convict on the competent verdict of theft where the charge is one of robbery. Theft is a generic offence that encompasses theft by false pretences. See Ex parte Minister of Justice: In re R v Gesa; R v De Jongh 1959 (1) SA 234 (A) at 239E – H where it was stated:

“If there was deception so fundamental that the will of the victim did not go with the act, there could be a taking and therefore larceny, called larceny by a trick. But if the deception was not so fundamental as wholly to nullify the voluntariness of the act, there was no room for larceny. Yet the deceiver’s conduct had to be punished and so the crime of obtaining goods by false pretences was devised.”

As was pointed out by RAMSBOTTOM J., in Dalrymple, Frank and Feinstein v. Friedman and Another, 1954 (4) S.A. 649 (W) at p. 664, it is not correct to say that our law’s treatment of both types of fraudulent acquisition of another’s goods – the larceny by a trick type and the obtaining by false pretences type – as theft by false pretences owes its origin to English practice. On the contrary in 1895 in R.v. Swart, 12 S.C. 421, De Villiers, C.J., stated that our law differs from the English law and has always treated facts covered by the English crime of obtaining by false pretences as theft. Ten years later in Rex v. Collins, 19 E.D.C. 163, Kotze, J.P., said that theft in our law has a much wider scope than the corresponding term in English law and that our crime of theft is wide enough to include the obtaining of goods by false pretences. The belief that our law of theft incorporated theft by false pretences under the influence of English law, a belief expressed, for instance, in Rex v.Mofoking, 1939 O.P.D. 117, may have been encouraged by the mistaken notion that there is in English law a crime of theft by false pretences (cf. Rex v. Hyland, 1924 T.P.D. 336 ).

It is true that the name of the English crime of obtaining by false pretences may well have suggested the use of the expression ‘theft by false pretences’ (cf. Transkeian Penal Code, secs. 191 to 193), but our law successfully resisted any tendency that there may have been to confine theft within the narrow limits of larceny.

Notwithstanding some of the old authorities it appears as if the Mia judgment is authority for the usefulness of the crime of theft by false pretences. More importantly, when on a charge of theft the evidence shows that the accused committed theft by false pretences, there is no reason why he/she should not be convicted of theft as charged.

In POLLEX The Archives, Retired Brig. Brig Dirk Lambrechts states the following; “According to Snyman, on p487 of his Criminal Law, third edition as published by Butterworths, the common law offence of fraud (Afrikaans: “gemenereg bedrog”) is defined as follows:

“Fraud is the unlawful and intentional making of a misrepresentation which causes actual prejudice or which is potentially prejudicial to another.”

And on p499 of the said Criminal Law appears the definition of the common law offence of theft by false pretences (Afrikaans: “diefstal deur valse voorwendsels”)*, namely –

“a person commits theft by false pretences if s/he unlawfully and intentionally obtains movable, corporeal property belonging to another with the consent of the person from whom s/he obtains it, such consent being given as a result of an intentional misrepresentation by the person committing the crime, and appropriates it”.

The misrepresentation (Afrikaans: “wanvoorstelling”) referred to in the definitions of common law fraud and in theft by false pretences supra*, may be made either by means of:

■ words;

■ conduct;

■ words and conduct;

■ writing;

■ omission (Afrikaans: “late”) or silence;

■ opinion;

■ puffing (Afrikaans: “ophemel/opjaag/reklame maak vir”); or

■ regarding a future event.

Bear also in mind that all cases of theft by false pretences* are in fact also fraud, although the converse is not so. The difference between the two is, inter alia, according to Snyman supra on p500 that fraud is completed the moment the misrepresentation has come to the notice of the representee.

For theft by false pretences to be completed, it is further required that the misrepresentation be followed by the handing over of movable corporeal property (Afrikaans: “roerende liggaamlike saak”) (like for instance a meal but not accommodation), whereas no such restriction as regards the object (Afrikaans: “voorwerp”) of the offence applies to fraud.

In case of doubt. Police officials must always remember that it is easier to explain why a police case docket had been closed, than to explain why a docket was not opened.

* In the light of remarks by Snyman supra on p499 and further, Burchell and Milton supra on p498, Hiemstra on p640 of his Suid-Afrikaanse Strafproses, fifth edition by Kriegler as published by Butterworths, as well as the authority quoted by the learned authors, it is doubtful whether the offence of theft by false pretences still exists in our law.”

Accordingly, it is suggested that such an offender be charged with theft by false pretences alternatively fraud or only with fraud, because, as was stated supra, all theft by false pretences is in fact fraud.